|

BORTH FROM CRAIG Y WYLFA

A SOCIAL HISTORY OF BORTH

One of the distressing aspects of family life in Britain in the 19th century was infant mortality. A glance at local records inform us that Captain David Hughes of the sloop Brothers, and his wife Elizabeth, buried Eliza age 2, another Eliza, again aged 2, John at 18, mariner James, drowned at 24 and mariner Evan drowned at 25. Another mariner, Evan Hughes, buried 1-year-old Hugh, 4-year-old Eliza and 5-year-old David. The women bore the brunt of the distress and made the funeral arrangements because the fathers were often away at sea; many of the seafarers never seeing the faces of their own children.

The often-primitive living conditions did not aid in these matters. Yet, to put this in historic perspective, one has to consider that Uppingham School in Rutland, was so unsanitary at the end of the 19th century that there was an outbreak of typhoid. This resulted in 300 pupils and teachers coming to live at Borth for just over a year in 1876-7, whilst comprehensive improvements were made to the school. During this time, 150 of the boys were billeted out amongst village families. Uppingham’s medical officer, Dr. Childs, remarked that he would have liked to have opened a practice at Borth, but that it would not have been financially viable as the village was such a healthy one. He even advocated it as a place of convalescence.

There were constant contradictions about the levels of hygiene at Borth. In 1873, three years prior to Uppingham School’s arrival, there was a series of damning reports about the lack of sanitation in the village. They mentioned that of 200 abodes, there were only 70 with privies, whilst others were deemed unfit for human habitation. Many of the dwellings were overcrowded with ten family members living in one room and the local school’s toilets were apparently a disgrace. Pigsties and manure heaps were everywhere in the village, which were deemed offensive and detrimental to health. Perhaps with this in mind, there was a specific clause written into the original deeds of Arequipa, a house built by Captain Thomas Rees stating that no pigs were to be kept on its land. All this implied that the village was an unhealthy place and could not possibly develop as a seaside resort. Despite this, householders had to make their own arrangements as a sewage scheme did not arrive for another hundred years, regardless of the seeming urgency of the ongoing debate.

Yet, whilst all the furore about the “vile state” of the village was going on, a contradictory letter from a “country vicar and constant visitor” commends the place to all who desire salubrity, quietness, a fine sea and beautiful countryside. “It is one of the healthiest places on the whole of the west coast of England or Wales, and I know that an eminent physician constantly recommends it to his patients. It has the most beautiful pure sea bathing, untainted with sewage on hard and perfectly level and safe sands…and has excellent lodging houses, which are quite above the average…it has clean water and excellent lodgings may be had of a humble description”

Sanitation aside, Borth inhabitants had to fight the sea from the shore as well. Prior to 1840 the shingle bank extended further out than it does today. There are records indicating that the sea side cottages had gardens on the beach side with a path all the way down the village beyond that. Erosion was obviously a threat and it became clear that after heavy storms in the second half of the 19th century that something had to be done to safeguard the village. Many cottages, especially the earth ones had been taken by the sea. The arrival of the railway not only bought new blood to the village, but also the notion that it could become a seaside resort.

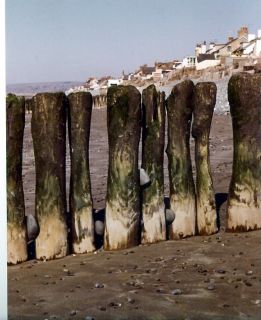

THE OLD SEA DEFENSES

Sea defenses were therefore necessary to protect the emerging resort. Initially they were built piecemeal, according to the availability of funds that were raised locally. The first comprehensive groyne systems extending out to the low water mark which ran along the length of the village were constructed by local carpenter John Beynon of Efailwen House around 1880. Each individual owner of properties that backed onto the sea organised their own pallisaded defences as many old photographs testify to. The sea took such an annual toll on the village, that the winter of 1899-1900 was regarded as a rarity in that it was free of shore damage; unlike the storm of 1896 when five dwellings were swept away, and a further dozen damaged. Again, it took nearly a century for a comprehensive defence system to be constructed.

THE SUNKEN FOREST

The herring dependant villagers precarious existence is nowhere more succinctly described than in Brief Glory. “Herring was the main harvest, for of gardens there were few if any, and the bog yielded nothing but peat for kindling; and since it was decreed by nature that even herring should only enter the bay during the season of storm around Michaelmas, it was no easy harvest home”. Although the marshland of Cors Fochno provided peat and turf for fuel, and rushes for thatching, the villagers had a certain instinctive aversion to it. This is exemplified in the folklore of “yr hen wrach ddu y figin” (the old black witch of the bog), which was created to ensure that the young avoided it as it possibly harboured pestilence. The annual winter bog burning of recent centuries, even though it was ostensibly to renew pastures, had far older roots reaching back to ancient times. Marshlands were known to harbour the ague, or as we know it, malaria, so it was very much cleansing by fire. In 1881, it was suggested by a local, that if Cors Fochno were drained it would much improve the health of the inhabitants as “no wonder there were so many weaklings, invalids and asthmatic persons in our midst, a few years ago we were annually visited by the ague”. Many marshy areas in Britain harboured malaria up until the 1840’s, with sporadic outbreaks up to the 1940’s. the superstitious also believed that a giant magic toad lived in the centre of Cors Fochno, and that one could confer with it about the future; that is if you were brave enough to seek out this amphibious oracle.

CORS FOCHNO

Researching the past can be fraught as often one is dealing with folklore and family tales that have been embellished over time. Information is checked as carefully as possible, but inevitably there are mistakes. Janet Greenwell relates a cautionary tale about her own investigations concerning one of her ancestors who was purported to have been a fiddler on Nelson’s Victory. Her exhaustive researches have revealed that, contrary to family lore, there was no Hugh Jones on any of Horatio Nelson’s vessels. The plausible explanation is that it was the Hugh Jones who commanded the local Borth sloop called Victory in 1829, who may have been a musician. The bane of researching mariners from small Welsh communities is the narrow range of Christian names and surnames. With some born in the same year it can be a minefield. Even the Borth locals had to add house names to differentiate between the many same name captains such as, Captain Davies Maesteg, Captain Davies Glanwern, Captain Davies Gloucester, Captain Davies Glendower and Captain Davies Bodina. It is difficult to keep track of family members using the same Christian name. The crew of the 37 ton sloop Morriston: Thomas Davies, master b.1816, Thomas Davies, mate b.1842 and Thomas Davies, ships boy b.1871, can cause confusion and matters become more convoluted when the latter two eventually became master mariners themselves. It is not easy to trace the careers of some other members of the Davies clan when one considers that on a voyage to the Baltic in 1878 on the 103 ton schooner Cecil Brindley, every crew-member was a Davies. They were David Davies b. 1838, master, John Davies b.1844, mate, David Davies b.1852, able seaman, James Davies b.1859, ordinary seaman and Richard Davies b.1864, ships boy.

THREE ANONYMOUS YOUNG BORTH MARINERS PHOTOGRAPHED IN SAN FRANCISCO

HOME

|